Fauna Forever meets Lifeworks to Improve Ecotourism for Local Amazon Community, by James Mailer and Dave Johnston

Asociación Fauna Forever, together with Lifeworks, an organisation which creates opportunities for teenagers from around the world to volunteer abroad, teamed up at the end of July (2010) with two main aims: to help young students experience the beauty and at times harsh reality of life in the Amazon and also, to help one particular local community on the Tambopata river, Baltimore, rebuild the ceiling of their school/community centre, as well as a rundown bird-hide managed by one of the community families, the Ramirez’s, located at one of the most vibrant parrot and macaw clay-licks in Tambopata – an attractive activity for visiting ecotourists. Ecotourism can provide a good income for anyone living in accessible parts of the Amazon rainforest, and if built with the right set of guidelines and ethical approach can become a sustainable practice for a community. This is also great news for the local environment because a job (or an entire family’s living in this case) in ecotourism will have far less of an impact on the environment than a job in gold mining, logging or hunting. Using land for ecotourism also means that the surrounding forest is expected to have a healthy abundance of wildlife and thus good ecotourism depends on a good level of forest protection.

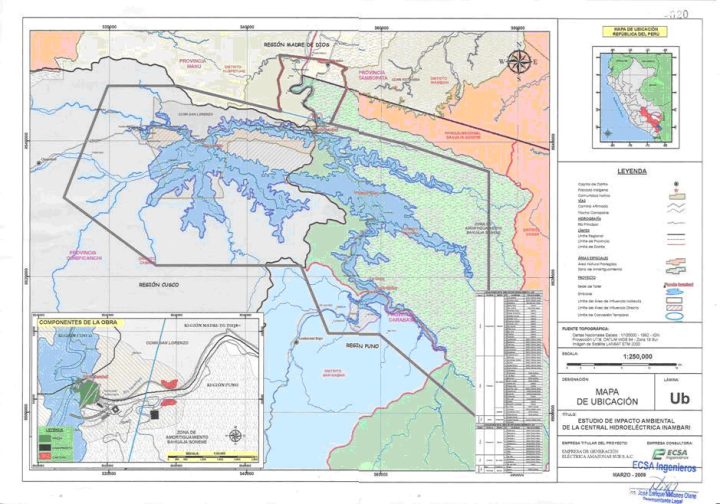

With these goals in mind Lifeworks met Fauna Forever (FF) in Puerto Maldonaldo (PEM); home to the FF team, capital of the Madre de Dios region of Peru, and just a short 30 minute flight from Cusco. More about the location: http://www.faunaforever.org/location.html

Dave and James, the FF representatives, welcomed Lifeworks coordinators Dan, Hilary and Willem, with their group of 18 students from the US, to the tiny jungle town. The students were between 13 and 17 years old.

The journey began with a whistle-stop tour of PEM including a supermarket stop, forest fruit ice-creams and a few interesting sights, the most poignant being the bridge that is currently being constructed over the Madre de Dios river. The bridge is the final piece of the new Trans-amazonica highway (http://www.bicusa.org/en/index.aspx) connecting the east coast of Brazil with the west coast of Peru and more so providing overland trade between Brazil and China. The traffic expected when this bridge is completed will create a wave of activity along the entire stretch of the highway with projections indicating that over a 30 year period 30 miles (50 kilometers) of rainforest will be destroyed each side of the highway as it cuts through pristine rainforest during the large majority of its stretch.

The group then set off from the Tambopata River port on a boat to Baltimore (http://www.baltimoreperu.org.pe/ingles/principal.htm) and after a breathtaking 4 hour journey upriver arrived at the El Gato guest house, pleasantly situated up the top of a tall river bank on the confluence of the El Gato and Tambopata rivers. The entire community is comprised of 22 inhabitants although the group was located at the home of the Ramirez family of 5. This was a long way from home for the students, without any luxuries such as hot water, windows, electricity or modern toilets. It was impressive to see how well most of them adopted their new environment with intrigue, while slowly submersing their mindset into ‘the wild’.

The most amazing part of the trip for many of the students was ‘the night walk’. Each evening the group filed slowly through the darkness behind Dave, with their flashlights swooping in all directions, encountering an array of creatures including an amazon tree boa, a tree runner, a southern tamandua, whiptail-scorpion spiders, caiman, dung beetles, owls, stick insects, bullet ants, leaf cutter ants, scorpions, tarantulas and much more. Holding a blunt-headed tree snake was a highlight, especially for those who had not wanted see a snake at all during their time in the jungle.

During the two full days at the community the students worked hard to ensure that the bird-hide was well constructed and that the ceiling of the school was completed. The group split into two which encouraged some friendly rivalry, mainly among the coordinators. Everyone did extremely well on both projects as they alternated day to day, especially considering the hot, humid, and mosquito ridden conditions! The difficulties all washed away very quickly with a swim in the El Gato waterfall at the end of each day, a perfect reward for everyone after much hard work. While washing and relaxation were the priorities of our daily swims, mud fights made staying clean difficult. When you can’t beat them though, you simply have to join in!

On the fourth day the group woke before light and said a sad farewell to delicious home-cooked meals by Mama Teresa, the sound of the waterfall, the star drenched nights, the fruit trees, our friend the Trumpeter bird, and all the sandflies! Off we travelled to Explorer’s Inn (www.explorersinn.com) which is situated downriver at the confluence of the La Torre and Tambapota. The trip was a fresh three hour ride through the new day’s tranquil sunrays breaking through the trees. Explorers Inn was built in 1975 and was the first ecolodge built within the Tambapota region. The students enjoyed the improved comfort and were able to relax after working at Baltimore. After an interesting butterfly talk by FF’s insect team coordinator, Ashley Anne Wick, there was a long walk to Lake Cocacocha, paddling around on two catamaran-style boats and getting up close and personal with some hefty black caiman which provided a fun-filled afternoon for all. The day was finished with a final night walk lead by FF’s herpetofauna team coordinator, Brian Crnobrna, and his ‘mad herper’ FF volunteer, Madison Wise, who both pointed out a couple of very pretty tree frogs.

The next day, after another early rise and a visit to the Explorer’s Inn parrot clay-lick, the group headed back to Puerto Maldonado to catch their flight to Cusco. There was just one final surprise waiting on the river bank. Some people (Dave) live years in the rainforest without seeing a big cat, but the group was lucky enough to catch a glimpse of a Puma on their final boat ride to town. Dave, unfortunately, was fast asleep and sat up too late to see it!

It had been a jam-packed few days of adventure, excitement and learning. Perhaps it will help to inspire some of the students to continue on, to learn more about the areas that interested them on the trip such as photography, anthropology, science or ecology. The curiosity and desire to learn about the rainforest shown by the students was the real beauty of this trip, and was a pleasure to witness. Time will tell how much the journey influenced the students and if they will perhaps choose to follow a path inline with our very own here in the Amazon, but we think one thing is for sure, that the hard work they put in to helping the local community, coupled with long walks and boat rides in the depths of the mighty Amazon rainforest, will stay with them forever.

leave a comment