The Inambari Dam Project: Nature vs. Power

By Chris Kirkby – Principal Investigator, Fauna Forever

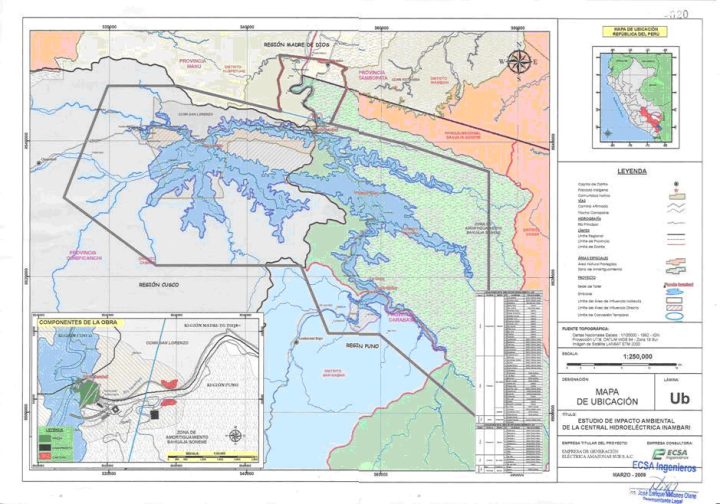

International media is once again turning its attention to the Amazon rainforests of south-eastern Peru, a spectacular wilderness area and biodiversity hotspot dominated by world famous national parks such as Manu and Bahuaja-Sonene where jaguars and giant otters still roam free and unaffected. What is drawing their interest? Yet another large-scale development project. First was the paving of the Interoceanica Highway, a westerly extension of the Trans Amazon Highway that crosses Brazil and which will facilitate cross-border trade. Now the Peruvian government plans to bring in a Brazilian consortium of companies (Ebasur) to build at a cost of US$4 Billion a 2,200-megawatt dam on the Inambari River, drowning 378 km2of life-rich tropical pre-montane forest located a stone’s throw from the Bahuaja-Sonene National Park (see map below). The benefits and impacts of this reservoir project are still being calculated, but most people in Peru already hold a strong opinion about it, one way or the other.

With regards to the benefits of the dam, the economic value is pretty easy to tot up as it would be dominated by the electricity produced, 80% of which would be exported to Brazil during the first decade to feed the growing industries in states such as Acre, Rondonia and Mato Grosso with the rest flowing into the Peruvian national grid to power the south of the country (details will be hammered out between the countries soon apparently). There are still no good published estimates of this benefit, at least not that we’ve been able to find, but it’s certain that someone will release it soon. There are also some additional benefits in terms of the tourism and recreational potential that a large reservoir would create, a reservoir that would be within 4-5 hours of Cusco (the tourist capital of Peru), within sight and easy access of snowcapped mountains (i.e. the Ausangate range) lined with azure-blue lakes and hotsprings at every turn, and one or two Cock-of-the-Rock (Rupicola peruviana) leks to boot. The building of dams also generates jobs of course, at least for the relatively short period it takes to build them, although in truth the value that one should consider is the premium in wages that workers would perceive above and beyond what they would normally be paid if they stayed in their existing jobs.

It is quite another matter putting monetary figures on the impacts, general upheaval and cost of headache pills that the building, flooding and subsequent operations will generate. And figures are what are needed as soon as possible, because local people, politicians and Peruvian society as a whole need to start taking decisions as money/value issues underpin strong arguments in this part of the world. Due to poor methodology in the past (or a simple lack of any method at all) the negative economic impacts of such mega-projects have largely been undervalued. Happily, some eager beavers have been developing tools to help calculate the costs of dams around the world (e.g. http://conservation-strategy.org/en/news/csf-launches-hydrocalculatortool).

Some of the more notable impacts include the forced movement of local people to higher ground and induced changes on farming practices. Ebasur and local district mayors estimate the number of people that will be directly and indirectly affected will be between 3,000-15,000. Some of these people welcome the prospect of being moved, others are not so inclined (and have already begun to protest in the streets), even though there is already talk about compensation, new schools and other government services. Not trivial are also the potential carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) emissions that the reservoir could generate over time from the decomposition of soil, sunken trees and other vegetation, each molecule of which would add to the climate change problem (particularly the methane) and so carries local, national and international costs (i.e. the dam may affect you too!). New or additional deforestation in areas near the reservoir, as a consequence of moving people to higher ground and as people from other areas migrate into the area to squat and clear land, will exacerbate this emissions impact. The water, sediment deposition, and flood regimes downstream of the dam (i.e. in Madre de Dios, Peru; Pando, Bolivia) will be severely affected, especially during the process of dam filling, which may take 2-3 years, not to mention the physical barrier to migrating fish that a 220m high wall of reinforced concrete will mean. Fish, fishermen, floodplain farmers (who rely on new, fertile sediment deposits on their lands each year, delivered to them by the annual floods during the rainy season) and other waterway users will all be affected in one way or another. Ethically controversial but significant none-the-less is that the restriction of sediment-flow will also leave thousands of miners downriver with a considerable deficit of gold to extract from riverbeds.

We hear a cost-benefit analysis, with values for all the above (and more hopefully) is still in the making, but will be published soon. As and when we get our hands on it, we will surely share some of its content here on the FFT blog.

So, Chris, which side of the fence do you stand at present? Good question Sir, where do I stand? Well, (i) if local people in the affected area can be moved to new housing in an orderly and planned fashion and sufficiently recompensed financially (for the headaches caused by moving house) and with good quality, organised housing and improved health and educational services; (ii) if sufficient research is undertaken well in advance to survey and translocate threatened wildlife species, and to estimate what the minimum discharges down-stream should be, during reservoir filling, in order to reduce impacts on say migratory fish and other aquatic animals in the Inambari river in Madre de Dios ; (iii) if the timber on hillsides and valleys that will lie below the future waterline can be extracted in as environmentally friendly a manner as possible (to reduce future CO2 and CH4 emissions from decomposition); (iv) if the Ministry of the Environment (that means you Antonio B.) can negotiate with (or force) both the companies that build the dam and those that will eventually operate it to regularly pay into an Inambari Forest Conservation and Development Fund (just made that name up on the spot) and simultaneously establish both the Ausangate-Inambari National Park and the Inambari Communal Reserve Network (just made those names up as well) to be situated upriver of the dam (which would together act to conserve the water quality and species rich parts of the catchment, would form a protected forest corridor between the Bahuaja Sonene National Park and the Amarakaeri Comunal Reserve [and hence to the Manu National Park], and would allow managed access by local people to certain natural resources); (v) if gold mining and coca growing activities further upriver on the Inambari River can be thoroughly regulated and brought under control (to reduce and one day eliminate the water pollution and deforestation that these activities generate); (vi) if a network of well manned park guard stations can be built on potential access routes leading from the roads, dam, rivers to the border of the Bahuaja Sonene National Park and the new protected areas to be established (to reduce illegal incursions into these areas); (vii) if only native species of fish are eventually allowed to be introduced into the resulting reservoir for fish farming or sport fishing (i.e. a BIG no-no to tilapia and carp); (viii) and if only quiet sailing boats (no speedboats and jet skis please) with yellow, green, or pink sails is the only type of pleasure craft allowed on the reservoir (maybe the colour code would be asking too much?); then I might at least toss a coin with a 50% chance of saying yes.

leave a comment